Community as Innovation Ecosystem

The Power of the Network Effect to Create Deep and Long Lasting Member Value

Summary

We know a great community when we experience it. There is a welcoming vibe, a feeling of belonging. It’s where we can bring our authentic selves and where debate is vigorous yet respectful, challenging yet connective.

The word community, however, is becoming like the words strategy or innovation: overused or misunderstood thereby losing its punch and power. It’s becoming code for kumbayi, everyone nods and agrees, my people are here. This is important, of course, but I think there’s much more to the story.

Great communities are vibrant and buzzing because there are problems that need to be solved and the best way for us to solve them is to work deeply over time in community with people like us, but also not like us. This is not an article about events, gatherings, volunteer committees, or networking. It is an article about the underlying architecture that makes these experiences indispensably valuable.

I lead the product community, a product development learning community designed specifically for associations. Let’s compare ideas and build something great.

Connections that Compound

“Transforming a system requires actions by multiple people with multiple capacities in multiple positions – not just by one person or organization. Radical engagement involves collaborating with unlike and unlikely others, making our differences productive – not just with people we like, and not forcing or feigning amiability or agreement. We do this by stepping up our engagement from just talking to also acting together.”

Adam Kahane

Community is not software and it’s not events. Community is not singular either (i.e. a global community of engineers). It is often driven by a stimulus (convenience, need, access to colleagues, learning new things, deals or discounts, etc.) or a catalyst, which is deeper and has the opportunity to effect change (i.e. a problem-solving team, a cross-departmental initiative to better serve members, or an impact network to connect experts in a particular niche).

An ecosystem is a web of interconnected organisms and their environment, where each element both depends on and supports the others. The health and diversity of each component strengthens the whole system.

In an association ecosystem, different types of members, activities, and resources create a self-reinforcing cycle of value creation. New members bring fresh perspectives and energy. Experienced members share knowledge and mentor newcomers. Volunteers organize events and initiatives. Industry experts contribute thought leadership. Sponsors provide resources. Each group both benefits from and contributes to the overall health of the community.

A network effect is when something becomes more valuable to everyone as more people use it. For associations, this means each new member can make the community more valuable for everyone. This is reflected in new perspectives, new experience, new learning, new revenue, or new impact. Over time, designed properly, the value of the community can grow exponentially.

I find this happens much less often in siloed initiatives like community-driven software, place-in-time events, volunteer committees, etc. In contrast, the network effect takes hold when people cross boundaries and nudge each other to build on simple ways of engagement. A truly powerful membership community creates network effects that can span multiple delivery modalities, with each mode reinforcing and amplifying the value of the others.

Instead of treating online communities, events, volunteering, and collaborative work as separate programs, leading associations design them as interconnected touch points that create compound value. A member's participation in one area enhances their experience and opportunities in all others. Here is some insight into how it could work:

Online to In-Person Amplification. Members who connect in online discussions can arrange to meet at conferences, turning digital relationships into face-to-face collaborations. Someone who shares expertise in an online forum might be invited to speak at a local chapter meeting, expanding their network geographically.

Events to Strategic Projects. Conversations that start during networking breaks at conferences can evolve into collaborative working groups tackling industry-wide challenges. Members who meet at one event often seek each other out at future gatherings, creating stronger ongoing relationships.

Volunteering as Network Catalyst. Members who volunteer together on committees or initiatives build trust and working relationships that extend far beyond the volunteer project. A marketing committee might include a consultant, an in-house marketer, and a vendor creating business opportunities that wouldn't have emerged otherwise.

Strategic Initiatives Creating Ongoing Connections. Members who collaborate on industry research, advocacy efforts, or problem-solving initiatives often maintain those professional relationships long after the project ends, referring business to each other and sharing opportunities.

For example, consider a healthcare administrators association. Say Sarah participates in an online discussion about patient satisfaction challenges. She connects there with Miguel, who mentions a successful program at his hospital. They arrange to meet at the annual conference, where Miguel introduces Sarah to three other administrators from his region who've tackled similar issues.

This newly formed group decides to collaborate on a best practices white paper. By working together, they discover complementary expertise: Sarah knows data analysis, Miguel understands patient communication, others bring policy knowledge. The white paper becomes so valuable that they're invited to present it at multiple regional events. These presentations lead to consulting opportunities, speaking engagements, and board positions. Sarah ends up hiring Miguel's hospital as a consultant for her system.

Design Principles for Cross-Modal Network Effects

Engaging people across modalities has the potential to have a powerful multiplier effect. This compounding effect draws people in and keeps them connected. Each interaction creates exponential possibilities rather than just additive value. The online connection led to the conference meeting, which led to the collaboration, which led to speaking opportunities, which led to business relationships, which led to new network connections at each step. Here are four design principles to help bring the network effect to life:

Continuity Systems: Create ways for connections made in one setting to easily continue in others. Event apps that connect to online communities, volunteer project teams that maintain ongoing forums, collaborative initiatives that include both virtual and in-person elements.

Cross-Pollination Opportunities: Actively facilitate connections between different participation modes. Invite online community leaders to speak at events, recruit event attendees for volunteer roles, showcase collaborative project results across all channels.

Recognition That Spans Modes: Acknowledge member contributions across all touch points, not just within silos. Someone who mentors online, volunteers for events, and contributes to strategic initiatives gets recognized holistically, encouraging multi-modal engagement.

Shared Outcomes: Design activities so that success in one area contributes to value in others. Research conducted by volunteer committees gets shared in online communities and presented at events. Event discussions generate content for online forums and spark ideas for new collaborative projects.

The network effect becomes exponential when members realize that their investment in any one aspect of community participation pays dividends across all their other interactions with the association and with fellow members. The magic happens when a community reaches critical mass.

This is the point where the value of being in the network becomes so obvious that people feel they can't afford NOT to be members. That's when growth accelerates because the community becomes essential rather than just nice-to-have. The key is designing your community so that member interactions create value for other members, not just for themselves. See my article Infinite Value: Fourteen Ways to Create Spinoff Products for Your Association for insight on leveraging ideas to spark community.

Connective Tissue

“People who join a community because they are interested in the domain often stay because they become emotionally connected to the community.”

Etienne Wenger, Richard McDermott, William M. Snyder

I love community for lots of reasons, but mostly because interacting with new people in new contexts can be the ultimate in idea sharing. In this way, community is learning. For this section, I borrow from the excellent book The Chessboard and the Web: Strategies of Connection in a Networked World by Anne-Marie Slaughter. The book is about the power of using chessboards (tactical moves to connect incrementally) and webs (powerful ecosystems in which we interact with others in novel and powerful ways).

Though both are important, I will focus on webs (which I reframe as ecosystems) that are designed for maximum connection and compounding value. The transition from chessboard to ecosystems offers new opportunities for associations to reimagine how they build and sustain communities of practice. Here are some thoughts on how to apply Slaughter's framework:

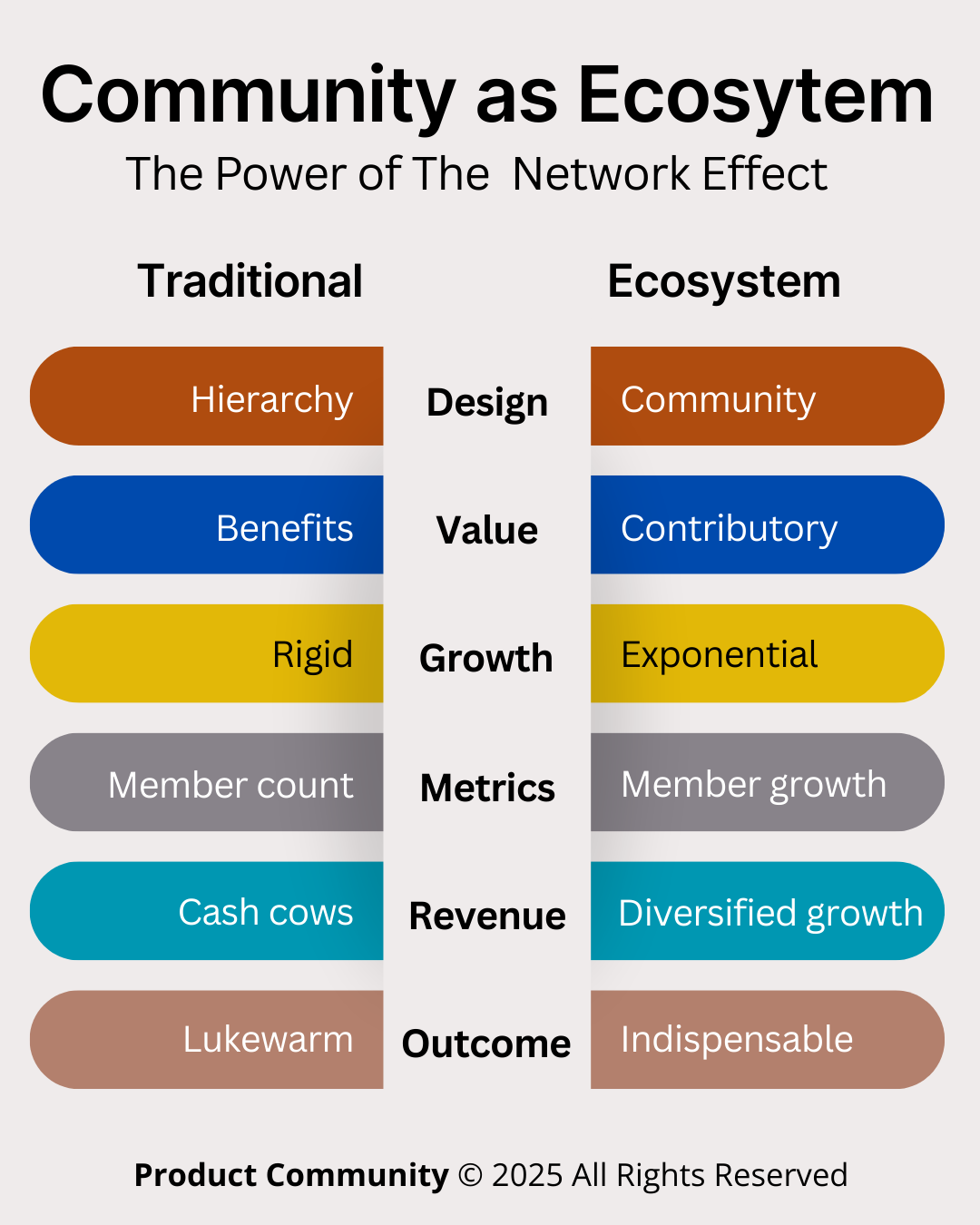

Shifting from Hierarchical to Network-Based Community Design

Traditional associations often structure communities of practice like mini-hierarchies, with designated leaders, formal committees, and top-down programming. An ecosystem suggests creating multiple interconnected nodes where members can connect directly with each other around shared interests, challenges, or expertise areas.

This means designing platforms and processes that facilitate peer-to-peer connections rather than just member-to-organization relationships. Think regional chapters that cross-pollinate, special interest groups that collaborate across traditional boundaries, or mentorship networks that create multiple relationship pathways.

Leveraging Connection as Currency

In network thinking, your value comes not just from what you know, but from who you can connect to whom. Associations can vastly enhance community by positioning themselves as super-connectors. This would entail identifying members with complementary needs, similar challenges, or synergistic expertise and actively facilitating those connections.

This might involve member matching systems, structured networking formats that go beyond business card exchanges, or creating connection challenges where members commit to making a certain number of meaningful introductions to fellow members each quarter.

Building Resilient, Self-Sustaining Networks

Unlike hierarchical programs that depend on staff coordination, well-designed networks become self-reinforcing. Members begin connecting and collaborating independently because the association has created the conditions and culture for organic relationship-building.

Practical approaches include training member volunteers as network weavers who actively look for connection opportunities, creating shared digital spaces where ongoing conversations can flourish beyond formal meetings, and developing recognition systems that reward members for facilitating connections for others.

Hybrid Approaches for Different Functions (order, latitude, and agency)

Slaughter emphasizes that successful organizations use both models strategically. Associations might maintain hierarchical efficiency for operational functions (membership processing, event logistics, financial management) while using network approaches for knowledge sharing, innovation, and community building.

For example, an association might use traditional project management for their annual conference but employ network thinking for year-round learning communities where members self-organize around emerging topics and challenges.

Creating Value Through Network Effects

The most powerful communities of practice generate value that increases exponentially with each new meaningful connection. Associations can design for these network effects by creating frameworks where member interactions produce shared resources: like thought leadership streams, collaborative knowledge bases, peer mentoring relationships, or innovation partnerships.

This involves moving beyond transactional thinking (i.e. what benefits does each member get for their dues?) toward generative thinking (i.e. how does each member's participation create more value for everyone else?).

Meeting New People

“The secret to getting people together is this: build your community with people, not for them.”

Bailey Richardson, Kevin Huynh, Kai Elmer Soto

Despite our value for it, deliberate community design is underutilized in associations.

Joining an association and becoming part of a robust community are two different things. Both should be natural and frictionless, but extra design, effort, and momentum goes into creating the conditions for making members to contribute willingly and engage meaningfully, deeply, and sustainably.

You can start by mapping your existing member networks to understand current connection patterns and identify gaps or opportunities. Experiment with network activation events that explicitly focus on relationship-building rather than content delivery. Develop systems to capture and share the knowledge that emerges from member interactions, making the invisible learning visible to the broader community.

Sustainable communities of practice aren't just about bringing people together. They're about creating conditions where people naturally want to stay connected and contribute to each other's success long after formal programs end. It’s our job to not only take the baton, but to pass it onto the next person.

I lead the product community; we are a learning community because we believe great relationships help us create the value our members want. Remember, product-led growth fuels connection. Join the product community and flip your destiny.

About the Author

James Young is founder and chief learning officer of the product community®. Jim is an engaging trainer and leading thinker in the worlds of associations, learning communities, and product development. Prior to starting the product community®, Jim served as Chief Learning Officer at both the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of College and University Planning. Please contact me for a conversation: james@productcommunity.us