Deep Understanding

A Framework to Identify and Respond to Member Problems

Summary

Reaching and fully engaging members is a primary focus of associations.

While it makes sense to do this through consistent relationship-building, our focus should be on deeply understanding our member’s struggles. I recently wrote about balancing purpose and revenue. I build on that article by addressing the underlying motivations for the problems members need solved.

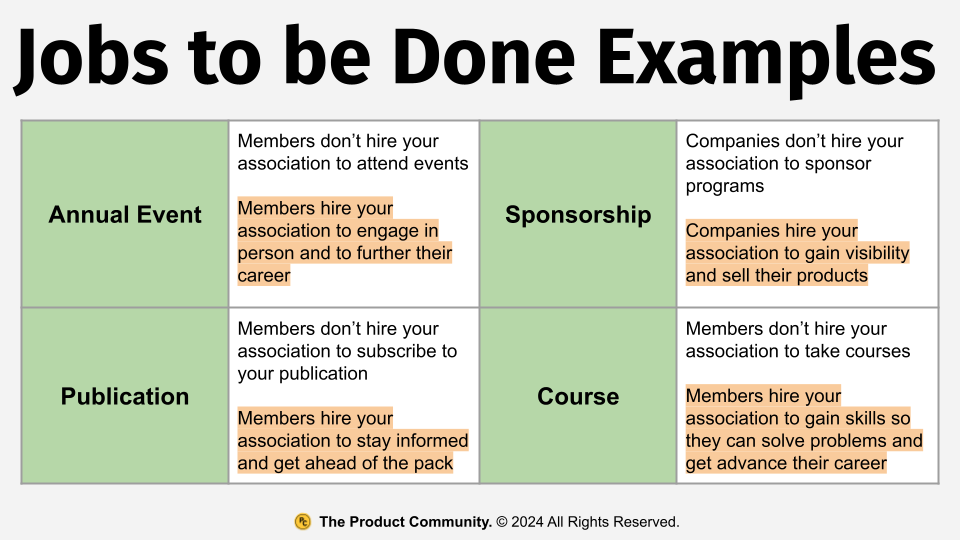

The Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) framework is a member-centric approach to understanding consumer behavior. It focuses on the underlying motivations and goals that drive people to "hire" a product or service, rather than on the member’s personality traits or an offering's features. In knowing this, we can create what members truly need so we can spark connections and create an appetite for joining and engaging.

The product community is a product development learning community designed specifically for associations.

The Importance of Understanding Member Problems

“Knowing more and more about customers — is taking us in the wrong direction. What we really need to home in on is the progress that the customer is trying to make in a given circumstance — what the customer hopes to accomplish. This is what we’ve come to call the job to be done.”

Clayton Christensen

Member insights are the lifeblood of association innovation. I’ve written several articles on understanding or learning from members:

This article focuses on the problems members need to solve. Why? There is a natural compulsion to offer new services to satisfy the needs of your community without fully understanding the problems the community actually needs solved.

Great products (offerings, programming, content, etc.) start with real problems. People buy products and services to get a job done. The key to success is accurately understanding the real job that members use your product for. The JTBD framework – popularized by Harvard Business Professor Clayton Christensen – argues that customers don't simply buy products or services; they "hire" them to perform specific jobs. These jobs are the progress that a customer is trying to make in a particular circumstance.

This entails understanding the problems that members have and translating these in a way in which we understand the underlying motivations. A problem refers to the underlying need, desire, or circumstance that motivates a customer to seek out and "hire" a product or service. It's not simply a surface-level issue, but rather the deeper goal or outcome the customer is trying to achieve. Key aspects of a problem:

It focuses on the customer's ultimate objective, not the means to achieve it.

It's often functional, emotional, or social in nature.

It exists independently of any specific solution.

Understanding it helps orgs innovate by addressing core customer needs.

Once we understand the problem, how do we use these insights for something actionable? Understanding the JTBD framework is important for several reasons:

It shifts focus from features to outcomes, helping associations better serve their members.

It aids in developing more targeted and effective products, services, and programs.

It can lead to increased member satisfaction and retention.

It provides a clear direction for innovation and growth strategy.

It helps in identifying new market opportunities and potential threats.

When we buy a product, we essentially “hire” it to help us do a job. If it does the job well, the next time we’re confronted with the same job, we tend to hire that product again. And if it does a crappy job, we “fire” it and look for an alternative.

This is one of our association’s most important dilemmas. By way of some examples, let’s see how it works.

How it Works

“We learned early that the outcome a person wants is much more important than the person themselves.”

Des Traynor

Understanding members does not drive innovation success; understanding member jobs does. A Job to be Done is the process a member goes through when they want to transform an existing situation into a preferred one, but cannot because there are constraints in the way.

Job identification: For associations, this involves understanding what members are truly trying to achieve. For example, a member of an association might not just want "networking opportunities," but rather "to build relationships that lead to career advancement." Example: An association for marketers might discover that their members' real job is "to stay ahead of rapidly evolving digital trends to remain competitive in their field.

Job statement: This clearly articulates the job in a structured format. Example: For a medical association, a job statement might be: "Help me access the latest research and treatment protocols so I can provide the best possible care to my patients and advance my career."

Job dimensions: Consider the functional, emotional, and social aspects of the job. Example: For a small business owners' association:

Functional – Provide tools and resources to improve business operations

Emotional – Offer support and reduce feelings of isolation

Social – Create opportunities for peer recognition and industry leadership

Job hierarchy: Recognizing main jobs and sub-jobs. Example: For a teachers' association:

Main job: Enhance teaching effectiveness

Sub-jobs:

Discover new pedagogical techniques

Learn to use educational technology

Manage classroom behavior effectively

Forces diagram: Analyzing forces that drive members towards or away from change. Example: For an association of real estate professionals:

Push of the present situation – Frustration with outdated listing systems

Pull of the new solution – Promise of AI-powered property matching

Anxiety of the new solution – Fear of technology replacing human expertise

Habit of the present – Comfort with familiar processes

Progress-making forces: Understanding what compels members to seek new solutions. Example: An association for accountants might identify that the rapid adoption of blockchain technology is driving members to seek education and certification.

Outcome expectations: Identifying criteria that members use to measure success. Example: For a project management association, members might evaluate success by:

Reduction in project completion time

Increase in client satisfaction scores

Number of successful project deliveries

Career advancement opportunities gained

Competitive analysis: Evaluating how well current solutions fulfill the job. Example: An association for graphic designers might assess:

How well their current workshops address emerging design software needs

The effectiveness of their job board compared to general job sites

The value of their networking events versus online professional communities

By applying these features of the JTBD framework, associations can gain deeper insights into their members' needs and motivations. This understanding helps to create a laser-focused value proposition, better targeted services, and improved retention. For instance, an association could use these insights to:

Redesign their professional development programs to focus on the most critical "jobs" identified by members

Create new membership tiers that align with different job hierarchies

Develop communication strategies that address the emotional and social dimensions of member jobs

Build new services that directly address unmet needs identified through the JTBD analysis

JTBD shifts our focus from guesswork to a deeper, more accurate sense of our members as real people who struggle with real problems. It is our job to create the conditions to help solve them.

Problem-Focused is People-Focused

“People are experts in their problem, not the solution.”

Paul Adams

The key to growing membership is to focus on member problems. It is the platform for empathy and relationship-building, the seed for engaged community-building, and the basis for focused innovation.

Most associations design new programs to meet evolving needs. On its head, this makes sense. But we focus way too much time on satisfying random wants and much less time on understanding (deeply and sustainably) the problems that members have (no less the underlying motivations that drive these problems).

Being problem-focused is an investment in people, connection, community, and growth.

I lead the product community; we are a learning community because we believe great relationships help us create the value our members want. Remember, product-led growth fuels connection. Join the product community and flip your destiny.

About the Author

James Young is founder and chief learning officer of the product community®. Jim is an engaging trainer and leading thinker in the worlds of associations, learning communities, and product development. Prior to starting the product community®, Jim served as Chief Learning Officer at both the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of College and University Planning. Please contact me for a conversation: james@productcommunity.us