Identifying Hidden Value

Leverage Your Portfolio to Evolve Your Association from a Vending Machine to an Indispensable Value Engine

Summary

A lot of associations operate like a series of isolated vending machines. Members feed quarters into the annual conference, webinar series, or certification program. Each transaction stands alone, each experience ends when the event concludes, each offering competes for the same limited attention and dollars. We tally revenue, count heads, and plan for next year’s lineup.

This model leaves enormous value on the table. When we view products as discrete units rather than as mineable possibilities, we miss important clues to help us better serve our members. A properly-designed portfolio is a strategic framework for organizing offerings in ways that reveal connections, identify opportunities, and create momentum. This article will show you how.

I lead the product community, a product development learning community designed specifically for associations. Let’s compare ideas and build something great.

Opportunity Under Our Noses

[We need] an organizing principle that enables us to identify and manage sources of competitive advantage in fast-changing markets. A framework that separates strategic portfolio decisions from scattered activity.

Paul Worthington

All associations need a portfolio (this is what we do), a high-level member journey model that maps engagement behaviors (this is how members experience value), and a system to help us identify and stitch together found value (this is how we satisfy member needs now and long into the future). Together, this is how we can create an indispensable value engine. An indispensable value engine is anticipatory and agile; it is a way of serving, but also learning from our members wants, needs, and behaviors. Well-designed, it creates belonging by positioning us for deep relevance. Well-executed (through iteration and experiments) we create loyal buyers who will tell their friends. A well-trod reminder: laser focus on understanding, empathizing, and reaching members. All value is a function of community. Let’s dig into this further.

The unmapped value in most association portfolios falls into three categories:

Underutilized content that could serve multiple markets

Disconnected experiences that could form longitudinal pathways

One-time transactions that could trigger recurring revenue.

Consider the annual conference, the massive investment of (staff, volunteer, financial) resources serving about 20% of membership for four days each year. We treat it as a revenue event with defined boundaries. Properly mapped, it could become an incubator for year-round engagement. For instance, a successful breakout session reveals demand for a quarterly workshop series. Hallway conversations expose gaps that become the foundation for a new community of practice. Speaker content gets repurposed into a podcast, transformed into bite-sized learning modules, or woven into a certification pathway. The conference generates relationships, content, and triggers that far outpace a standalone event.

Mapping value makes visible the connections between current offerings and new opportunities. It requires seeing our portfolio through multiple lenses. Through the lens of content, where we identify reusable assets that can be remixed, repurposed, and extended across different formats and audiences. Through the lens of member journeys where we see how offerings could stack and support member progress over time. Through the lens of the Growth-Share Matrix where we determine which offerings are cash cows subsidizing innovation, which are dogs draining resources, which are question marks with potential, and which are stars that drive growth.

The practical work of value mapping starts with assembling a cross-functional team (finance, education, membership, marketing, volunteers, etc.) willing to challenge assumptions about what makes something valuable. Together, this team creates a comprehensive view of the portfolio that goes beyond departmental silos to reveal systemic opportunities. With a team assembled, mapping moves through stages. First comes inventory: what do we offer, who creates it, who consumes it, what does it cost to produce, what revenue does it generate, and what outcomes does it create? Inventorying our offerings forces discipline and reveals how unmapped value can create new opportunities.

The next step is taxonomy or organizing offerings into logical categories, identifying product lines and product components, and creating a shared language for describing what we do. A taxonomy transforms a messy list into a structured framework. The taxonomy makes patterns visible and these patterns reveal interdependencies disguised as opportunities: which offerings naturally connect to each other, where do member pathways emerge organically, and what content could be leveraged intentionally? We discover that members who attend the annual meeting are four times more likely to join a local chapter. This insight can drive strategy. We can redesign the conference to facilitate local connections, create bridge programming that connects attendees to chapter activities, and measure success by the resulting conversions.

Finding Value in the Gaps

Hidden value often lives in the gaps of our current offerings. Mapping can reveal natural next steps, member journeys opportunities, and unaddressed needs. A gap analysis examines the portfolio through the member’s lens: what should come before this offering to prepare members for success? What should come after to extend the value? What related needs remain unmet? An engineering association maps its product portfolio and realizes it offers both entry-level and advanced technical courses, but nothing in between. Members take the introductory course, want more, find nothing suitable, and disengage. The gap is invisible when looking at individual products but glaring when mapping the portfolio as a member journey.

The criteria for identifying hidden value work at multiple levels. At the individual offering level, we ask: does this product stand alone or could it be the foundation for a product line? Could components be extracted and repackaged for different markets? Are there untapped modalities, like transforming in-person workshops into virtual cohorts or distilling dense reports into infographics? At the portfolio level: can cash cows fund innovation? Do question marks evolve into stars? Are we leveraging our content, or recreating from scratch what already exists? Do our offerings create network effects where each new participant makes the experience more valuable for everyone else?

Mapping for Leverage

“Your customers are your North Star. Listen to their feedback, adapt to their needs, and never lose sight of the value you’re providing. If you’re not solving their problems, someone else will.”

Guy Kawasaki

The Growth-Share Matrix is a tool to help us map value. It was developed by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and can be used to categorize association products into four quadrants based on their market share and market growth rate. Each quadrant represents a different strategic approach for managing these products.

Cash cows are typically membership dues, annual conferences, and established certification programs. They generate reliable revenue in mature markets, but they rarely drive growth. Despite the comfort of reliable revenue, they are double-edged swords. As they often generate up to 90% (or more of our annual revenue), we cater to, and build around, them in a way that blunts broad-based engagement and makes it hard to innovate. The cash cow model is the opposite of healthy, growth revenue. But, because it brings in the money it becomes sacrosanct. This is why we need to leverage, tap, or extend our cash cows to the hilt. They are underutilized and untapped sources of value.

For instance: how do we leverage their stability to fund innovation or extend their relevance by combining it with other offerings? For instance, a mature certification program generates steady revenue but has declining enrollment. Rather than letting it age into irrelevance, we can map connections to other content, create stackable credentials, and position it as the capstone of a longitudinal learning pathway. The cash cow remains a revenue driver while sparking new engagement across the portfolio.

Transforming Dogs Into Opportunities

Dogs are low-performing offerings in low-growth markets, the programs we keep running out of inertia rather than intent. Mapping value among dogs means asking hard questions: could this offering serve a different market where it would have higher impact? Could it be radically simplified to reduce costs while maintaining value? Or should we stop doing it entirely and redirect those resources toward higher-potential opportunities? An association runs a monthly webinar series that consistently attracts small audiences and requires significant staff time. Value mapping reveals that the dozen people who show up could be ideal candidates for a peer learning circle. The hidden value was in recognizing that small, committed audiences want depth and community, not broadcast content.

Nurturing Question Marks Into Stars

Question marks are offerings in high-growth markets where we have low market share; they are experiments and emerging programs with uncertain futures. They are prospects to identify possible opportunities. For instance, a trade association launches a podcast about industry trends. Downloads are modest but growing. Mapping value means examining direct revenue and its role in the broader portfolio. Are podcast listeners likely to attend events? Does the podcast attract younger members? Do episode topics signal ideas for new programs? The question mark’s hidden value can reveal emerging needs and new audiences. We can, therefore, think of the podcast as market research, a membership acquisition channel, and an entree to feed other parts of the portfolio.

Stars are high-growth offerings in high-growth markets, the programs that attract enthusiastic participation and drive expansion. Many associations lack stars because we focus on stable cash cows. Mapping value means asking: where should we invest to create stars? What emerging needs can we meet that competitors cannot? For instance, a design association recognizes that young professionals are hungry for collaborative projects that build their portfolios while creating real impact. They launch a year-long program where cross-functional teams tackle challenges submitted by nonprofits. The program attracts waiting lists, generates portfolio-worthy outcomes, creates strong alumni networks, and becomes a talent pipeline for employers who sponsor the initiative. This star emerges from mapping the portfolio, identifying a gap, and designing something aligned with a genuine market opportunity.

From Episodes to Journeys

We don’t value things; we value what they mean to us.

Kartikey Sengar

The transition from episodic engagement to longitudinal pathways is where value mapping delivers its greatest impact. Traditional associations deliver value in discrete units: events, courses, membership. As they stand alone, we constantly work to spark the next transaction. In contrast, mapped portfolios reveal natural progressions. Each touchpoint builds on the previous one, and the association’s role shifts, over time, to journey architect.

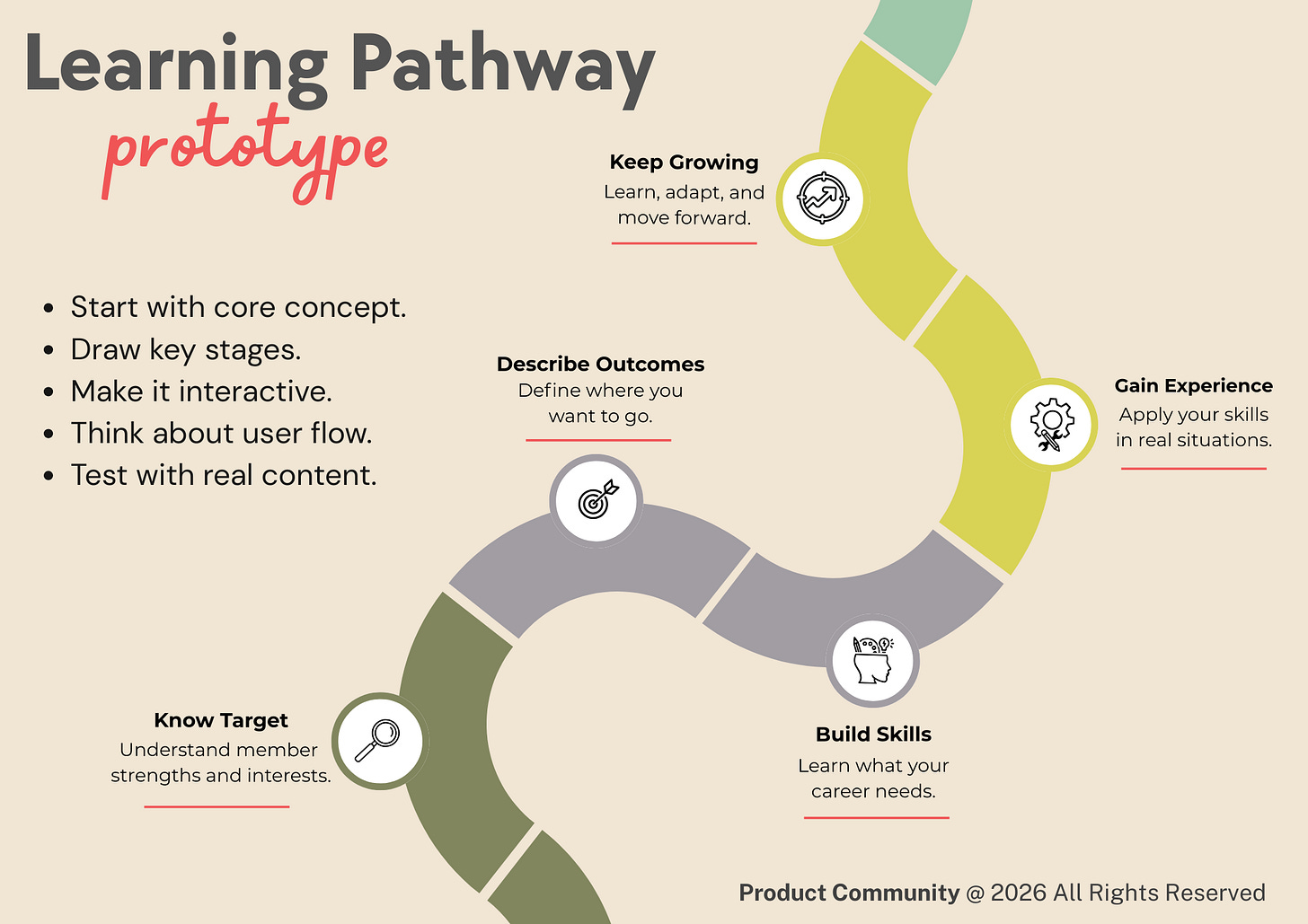

This longitudinal approach fundamentally changes how we think about revenue. In a transactional model, revenue comes from selling individual products to as many people as possible. In a pathway model, revenue comes from deepening engagement over time with members who find increasing value. For instance, an association could map its portfolio and redesigns around three pathways: getting started, building expertise, and leading the profession. Each pathway contains multiple touch points, some free, some paid, some synchronous, some asynchronous. Members enter a pathway where the conference is one milestone among many. We move from tracking attendance to measuring how participants progress from awareness to engagement to contribution. Revenue per member increases because members engage more deeply across the portfolio. This graphic and an example learning pathway prototype comes from my article Build What Members Want.

Creating good revenue through value mapping means designing offerings that trigger more engagement. A workshop that concludes with participants exchanging contact information generates less value than one that launches a structured peer learning circle scheduled to meet monthly for a year. The mapped portfolio asks at every touchpoint: what’s the natural next step and have we designed for it? Hidden value often lives in these transitions. Members want to continue engaging, but the architecture isn’t there to support it. Building that architecture requires connecting and extending what already exists.

Mapping value also means socializing an org-wide innovation habit. Instead of spotty innovation driven by pet projects, it becomes embedded in the portfolio. Regular reviews ask: what are we learning from our question marks? Where do our stars need investment to maintain momentum? How can we extend our cash cows while they’re still strong? What dogs should we sunset to free resources? This rhythm makes innovation continuous rather than episodic. Staff and volunteers develop fluency in portfolio thinking. Rather than defending their individual programs, they contribute to systemic portfolio health.

This innovation habit requires creating feedback loops between the portfolio and the community it serves. Continuous discovery means constantly listening to member needs, testing assumptions, and adjusting offerings based on what we learn. The portfolio evolves as the community evolves. This can only happen because the portfolio is mapped and regularly reviewed. We get better at spotting trends early and can respond strategically.

The Compound Effect of Mapped Value

When you treat people as people, you align the touch points: marketing creates relevant invitations, community fosters connection, product delivers value, and customer success drives outcomes together.

Joshua Zerkel

The compound effect of mapped value helps transform association economics. In the transactional model, each product must justify itself individually, leading to bloated portfolios where marginal offerings exist to cover direct costs. In the mapped portfolio model, offerings are evaluated on their contribution to the system. A low-revenue offering might be retained because it serves as a critical entry point, converting prospects into members who then engage with higher-value offerings. Another might be eliminated despite positive revenue because it cannibalizes attention from more strategic priorities.

Perhaps most importantly, mapping value positions us as community curators. Members join because we help them navigate their professional journey, connect with peers, and make progress on problems that matter. The mapped portfolio makes this journey visible because we design clear pathways illuminated by the value map. Engagement becomes longitudinal, relationships deepen, and the community effect compounds. Revenue becomes an outcome of the genuine value members experience.

About the Author

James Young is founder and chief learning officer of the product community®. Jim is an engaging trainer and leading thinker in the worlds of associations, learning communities, and product development. Prior to starting the product community®, Jim served as Chief Learning Officer at both the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of College and University Planning. Please contact me for a conversation: james@productcommunity.us